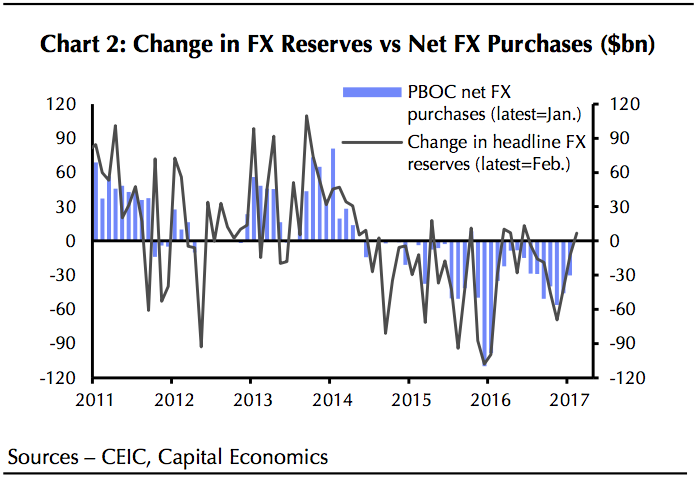

Throughout his campaign for president, Donald Trump promised to name China a currency manipulatoras soon as he got the chance. While he hasn’t done that yet, he also hasn’t let go of the complaint that China is suppressing the value of its currency to make its exports more competitive. Last month he said it is a “grand champion” at manipulating its currency. For most of last year, the evidence didn’t support Trump’s claims. The yuan was falling, but that was because Chinese businesses and investors were moving capital out of the country. If China did intervene it was to keep the currency from falling too fast. A big clue toward this was that China’s foreign-exchange reserves were tumbling. They fell for eight straight months. That just changed. Data published by the People’s Bank of China on Tuesday showed the country’s FX reserves rose by $6.92 billion to $3.005 trillion during February, making for the first increase since June. Economists surveyed by Bloomberg were expecting that number to fall to $2.969 billion, on average.

“Our model suggests that valuation effects from fluctuations in exchange rates and bond prices should, if anything, have reduced the value of the reserves,” wrote Capital Economics economists Julian Evans-Pritchard and Mark Williams in a note sent out to clients after the data was released. “At face value then, it appears that the People’s Bank (PBOC) purchased rather than sold foreign exchange last month for the first time since October 2015.” [Emphasis is ours]. According to Evans-Pritchard and Williams, this marks a “striking shift” and suggests “the charge that China has been intervening to weaken its currency, may be justified,” at least for the month of February. They believe Tuesday’s data could “create tensions with the Trump administration.”

The Treasury Department’s Currency Report, and an opportunity to slap the currency manipulator label on China, is due out next month. The tag isn’t immediately punitive – the US has to spend some time negotiating with China over the issue before it then begins to impose some low-level sanctions against the country. The last time China had the label was from 1992 to 1994. In order for that to happen, three conditions must be met, according to the Treasury Department.

The country must have a significant bilateral trade surplus with the US (China had a $347 billion trade surplus with the US in 2016). The country has a “material” currency account surplus (For the first nine months of 2016 China’s current account surplus hit $172.7 billion). The country is engaged in persistent one-sided intervention in the foreign exchange market.

While the first two conditions are arguably being met, the third is iffy. Even if this is the beginning of a trend, one month of data is hardly enough to make the case that China is engaging in “persistent one-sided intervention.” Of course, the Trump administration might not be stopped by that last argument, or for that matter what existing US laws state about what it can do with the label. Here’s what Deutsche Bank’s economist wrote about the issue last month, as they speculated that the ‘currency manipulator’ tag could come soon: “This has been a consistent campaign promise and he has demonstrated since taking office his determination to deliver on his promises, however controversial,” they wrote. “Existing US law and its application by the Treasury in recent years are unlikely to satisfy the President’s desire for strong penalties for unfair trade, so we anticipate that the proposed measures could go far beyond what has thought possible even a few weeks ago.”